One of the great things about games is their power to tell stories. Whether it's knights fighting dragons or German bureaucrats buying merchant houses, games can engross you in narratives that you create with your friends. My favourite game stories are those with troubling historical

settings: those periods when reprehensible actions led to positive

effects or good intentions created disasters. Unfortunately, most games

get in the way of these narratives by having contrivances that may make

for fun experiences but break the suspension of disbelief. Why are the

Catan's harbours built before anybody's settled the island? Why are the

richest real estate barons in New Jersey forced to stay at each other's

hotels? All too often, game designers focus on the puzzle-like and

competitive aspects of games, ignoring their storytelling potential.

It's possible to design a game that's interesting because of both the

challenge it poses and the stories it tells. It's hard, but when it

succeeds, it's amazing. Not attempting to create that connection between

the game, the players and a story is a missed opportunity.

One of the great things about games is their power to tell stories. Whether it's knights fighting dragons or German bureaucrats buying merchant houses, games can engross you in narratives that you create with your friends. My favourite game stories are those with troubling historical

settings: those periods when reprehensible actions led to positive

effects or good intentions created disasters. Unfortunately, most games

get in the way of these narratives by having contrivances that may make

for fun experiences but break the suspension of disbelief. Why are the

Catan's harbours built before anybody's settled the island? Why are the

richest real estate barons in New Jersey forced to stay at each other's

hotels? All too often, game designers focus on the puzzle-like and

competitive aspects of games, ignoring their storytelling potential.

It's possible to design a game that's interesting because of both the

challenge it poses and the stories it tells. It's hard, but when it

succeeds, it's amazing. Not attempting to create that connection between

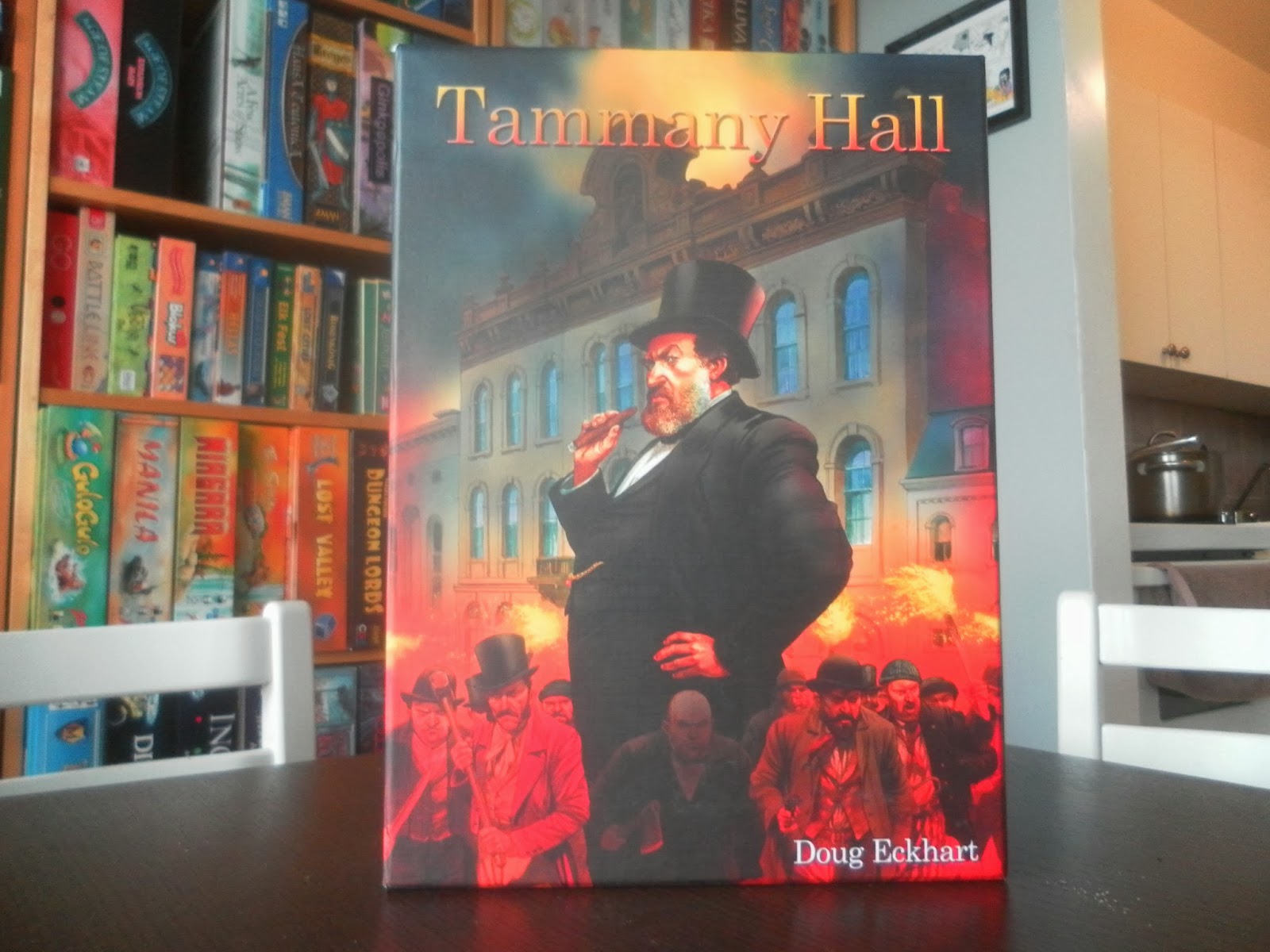

the game, the players and a story is a missed opportunity. No game capitalizes on that opportunity as well as Tammany Hall. Nothing feels shoehorned in; every aspect of the game flows naturally and logically from its setting and characters without sacrificing any strategic depth. The fact that the setting is 19th century New York City and the characters are corrupt politicians who stop at nothing to gain power makes me wonder whether Doug Eckhart designed the game specifically for me.